Accessory Dwelling Unit

Time period: 20th century to present day

Location: Suburbs

In places that allow them, Accessory Dwelling Units are a way to have

more than one home on a lot that is zoned only for one regular full-size

home.

ADUs are a second, smaller home (typically studio, 1-bedroom, or 2-bedroom) on the same property as a full size house. They're also called accessory apartments, secondary units, in-law suites, and granny flats. Hawaii calls them Ohana dwellings.

In zoning and building codes, accessory uses are minor uses that are allowed as part of a larger project, even if the zoning or occupancy type does not normally allow it. An example of an accessory use is the manager's office of an apartment building, which is allowed in a residential zone even though it's an office use. ADU's are a similar regulatory reform to allow two homes on a single family lot, without changing it to duplex zoning.

Examples of types of ADUs.

Each type of ADU has advantages and disadvantages.

- Detached: Greatest amount of privacy and can be prefab, but typically most expensive and needs the most space.

- Attached to house: Cheaper than detached, and often zoning allows more height, but blocks windows on existing house.

- Basement or lower level conversion: Can be economical if basement is already finished, or if foundation needs work anyway, but low ceilings may require raising of house or digging down to meet minimum ceiling height. This is a popular option for unpermitted ADUs since it can be easily disguised as a side door to the house.

- Converted garage: Often the cheapest way to build an ADU, but may require replacement parking to be provided depending on zoning.

- On top of garage: Preserves both the parking and the yard, but more costly than a garage conversion.

- Attic or upper level conversion/addition: Can work on smaller lots that don't have a garage or much yard space, but may run into zoning issues with height limit.

Since an ADU is small and often hidden behind the main house, the

visual change to the neighborhood is minimal. This has made ADU

legislation a common choice as a first step of zoning reform, when the

political will to allow regular apartment buildings in single family

zones is not yet there. Still, efforts to allow ADUs have often been

controversial, because the main issue was never about how the

neighborhood looks, but who gets to live in it.

The house in the back - an old concept

Residential areas in cities using the grid system featured repeating blocks of narrow but deep lots - typically 25-50 feet wide and 100-150 feet deep. Houses were built on the front of the lot. The backyard would initially be used for gardens or keeping livestock, and as the city grew, would be filled in with new buildings, such as additional houses.

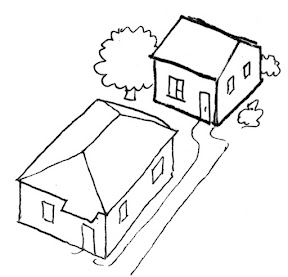

Evolution of a lot:

1. House

2. House with accessory unit

3. Two houses

4. Townhouse

5. Mid-rise apartment building

Racism and Zoning

The late 1800s and early 1900s were a period of rapid urbanization in the United States. Cities grew rapidly as the number of factory jobs increased. This was a period of high immigration, when large numbers of immigrants entered the country through Ellis Island. In the South, racists forced Reconstruction to end, which was followed by an increase in violence and discriminatory Jim Crow laws, causing many Black people to move to northern cities in search of better opportunities and safety. This accelerated during World War I when immigration from Europe ended while factories needed even more workers.

To keep newcomers out of their neighborhoods, existing residents first used racial zoning, which regulated who could live where. Exclusion was done not just based on race, but also religion and ancestry (aimed at immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe). Exceptions were written into the law for live-in domestic servants.

Racial zoning was banned by the Supreme Court in 1917. Exclusionary communities continued to use other methods to keep neighborhoods segregated, such as violence, discriminatory mortgage practices, restrictive covenants on property deeds that limited who could buy the property, and zoning laws that didn't mention race but had the same practical effect, such as single family zoning.

While single family zoning appears to be racially neutral, because there were (and still are) massive racial differences in income and wealth, by banning cheaper forms of housing such as apartments or rooming houses, a community could get to the same result as racial zoning. Some cities went a step further, with zoning laws that required that new houses be large, with a minimum size requirement. Like racial zoning, single family zoning was challenged in the courts, however, this time the Supreme Court upheld the law in the 1926 case Euclid v. Ambler.

The ADU goes into hiding

Banning multifamily housing did not make the need for it go away, instead, it created an underground market. Low income residents continued to seek out small homes, and property owners met that need by building unpermitted ADUs. For example, in San Francisco, by 1960 there were an estimated 20,000-30,000 unpermitted ADUs, making up almost 1 in 10 homes in the city. Unable to kick out that many people, the city tolerated but continued to shut down unpermitted ADUs case-by-case and evict their residents when neighbors complained. It wasn't until 2013 that San Francisco passed a local law that encouraged owners to legalize their ADUs and bring them up to code.

The return of the ADU

ADUs made their formal return in the 1990s and 21st century as part of the larger New Urbanism movement to create communities that are less car dependent and isolating. To overcome NIMBYism, New Urbanism applied a political strategy of describing ADUs, mixed use zoning, and other ideas not as a radical new change, but simply a return to traditional neighborhood design.

In a further attempt to reduce opposition, politicians and planners often called them "in-law units" or "granny flats", suggesting that the residents would be elderly family members, rather than outsiders Today, names of that sort are discouraged, as it is a Fair Housing Act violation to advertise housing as being for a certain age group, unless it is senior housing.

There is some truth to it though - senior citizens make up a significant number of ADU residents, though more often they are the owners of ADUs rather than the occupant. AARP, an organization advocating for people age 50 and up, is a major supporter of ADU legislation. Common reasons older adults build ADUs include:

- Providing a home for an elderly parent.

- Rental ADU for retirement income.

- A home for a live-in attendant.

- Aging in place: a smaller

single-story home to move into, without having to leave the neighborhood. That said, fully accessible ADUs are rare.

Example of 500 square foot one-bedroom ADUs. Long and narrow floorplans are more popular for prefab ADUs since they can be transported on a truck in one piece, while square floorplans are more compact.

Limits and Limitations

In practice, a 2014 survey of ADUs in Portland, Oregon found that the most common age group of ADU residents were young adults. Families with children are rare: 2/3 of ADUs had just one resident, and only 1% had three or more residents. This is because the size of ADUs is limited by law - Portland's code limits them to a maximum size of 800 square feet in most cases, the size of a compact two-bedroom apartment. Most other ADU laws have similar limits. Conveniently for NIMBYs and policymakers attempting to please them, this means that ADUs add to the tax base, while having little impact on the number or average household income of K-12 students.

Other common limitations include owner-occupancy requirements that require the property owner to live in either the main house or the ADU. At the same time, most places also only allow ADUs to be rentals, not allowing them to be sold separate from the main house. This "you can rent here but you can't be a homeowner here" model of most ADU law can come across as an uncomfortable echo of racial covenants and the "servants only" exemptions to racial zoning.

Requiring a homeowner as landlord business model limits the number of ADUs being built (not everyone can afford to build one, or wants to be a landlord), while also makes it more likely that the owner rents it to someone they know, rather than treat it like a commodity on the open market.

All this makes it easier to get communities to accept ADUs, but also makes them less effective at ending exclusion and segregation. That said, the general trend of ADU legislation is of continuous expansion, with new laws every couple of years allowing more options. For example, in Seattle, ADUs can be up to 1,000 square feet, and can be sold separately as condos. In California, owner-occupancy is no longer required, and ADU law paved the way for Senate Bill 9, which allows adding regular houses to a lot.

Example of a 600 square foot two-bedroom ADU.

This is a compact layout that can be prefab and brought in on a truck.

Example of a 900 square foot, two-story two-bedroom ADU.

Short Term Rentals

While most ADUs are used as permanent housing, some homeowners use them as short term rentals such as Airbnb. There are a few reasons for this - short term rentals can be more profitable, the owner may want to use the ADU for a family member part of the year, or the owner is planning to move into the ADU relatively soon and doesn't want a long term tenant. STR income can help make it easier to finance an ADU, but neighbors often do not like STR's due to perceptions that short term vacation guests are more likely to cause noise problems than a permanent resident. There's also more political pressure to solve the housing shortage than a vacation rental shortage.

Some governments have responded by banning the use of new ADUs as short term rentals, while others, such as Berkeley, allow a separate STR guest room without a kitchen to be built in addition to the ADU.

The ADU Industry

The building industry has two main sides to it, and ADUs don't neatly fit into either.

On one side, there's custom residential - custom homes designed for wealthy people for who this is usually their first construction project. Architects and contractors who work in this space have more creative freedom, but also have to do a lot of hand holding, and occassionally even marriage counseling.

On the other, there's commercial, which is everything larger than a house. The client is either a business or institution. Buildings have some customization to fit the site and specific needs, but are much more standardized.

Since the typical ADU client is a middle class homeowner, ADU builders have to deal with both inexperience and a tight budget. This provides an opening for new businesses to get in on the action.

The first one is small contractors that previously specialized in remodels, which aren't that different from a conversion or an attached ADU project. The other is the prefab detached ADU. Similar to mobile homes and other manufactured housing, these are built offsite and moved into place by truck and crane.

Prefabs are great for those who aren't sure what they want, as they can view photos of examples and even visit showrooms with fully furnished ADUs to help understand the space before deciding what to build. They work well with pre-approved ADU programs, where someone can go to the permit department, pick an ADU, and leave with a permit on the same day.

Ways to make it easier to build ADUs

Zoning obstacles that can be removed

- Minimum lot size requirements

- Minimum yard/setback requirements

- Parking requirements

- Height limits

- Requirements that ADUs need to be attached or detached from house

- Square feet maximums for the ADU

Making it easier to get approvals

- Removing the need to go through Design Review

- Approval by city staff instead of having to go through public hearings (Ministerial approval)

- Pre-Approved ADU Plans

- Laws that override Homeowner Associations (HOA) bans on ADUs

Increasing the attractiveness of investing in ADUs

- ADU construction loans

- Removing requirement that main house has to be owner occupied

- Allow more than one ADU per lot

- Allowing ADUs to be sold separate from the house

Lowering the costs

- Removing or lowering permit fees, development impact fees, and utility connection fees

- Not requiring existing house to be upgraded to modern code when an ADU is added

- Subsidies for design and other pre-construction costs

- Allowing ADU to share kitchen or bathroom with main house

See the article on California ADUs for an example of the evolution of ADU regulations

Data

- Density: 5-20+ units/acre

- Typical Lot Size: 4,000 to 10,000 square feet

- Typical Zoning: Single Family Residential, Low Density Residential

- Construction Type: Wood Frame

- Resident Type: Family Member or Rental. May be owner occupied in places where condo ADUs are allowed.

Where to build

- Single family zones with high housing demand

Further Reading

Origins of single family zoning https://medium.com/@markvalli/the-origins-of-single-family-zoning-in-the-united-states-cca2ed73ac92

Racism and zoning https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/goldwyn17/files/2017/01/silver-racialoriginsofzoning.pdf

Euclid v. Ambler case https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep272/usrep272365/usrep272365.pdf

History of ADUs https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/adu.pdf

Background on ADU policy in San Francisco up through 2006 https://www.spur.org/publications/spur-report/2006-06-01/secondary-units

Current San Francisco for legalizing an unpermitted unit https://sf.gov/step-by-step/legalize-unit-your-home

AARP model ADU ordinance https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/housing/info-2021/adu-model-state-act-and-local-ordinance.html

Data on who lives in ADUs in Portland https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1040&context=trec_seminar

Data on Seattle ADUs https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/OPCD/OngoingInitiatives/EncouragingBackyardCottages/OPCD-ADUAnnualReport2022.pdf

Seattle ADU regulations https://aduniverse-seattlecitygis.hub.arcgis.com/pages/code

Example of ADUs in Seattle https://aduniverse-seattlecitygis.hub.arcgis.com/pages/gallery

Comparison of ADU laws in different states https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/state-accessory-dwelling-unit-laws

Conservative conspiracy theorists complaining about ADU's https://www.curbed.com/2023/08/qanon-huntington-long-island-adu-conspiracy.html

Ohana units in Hawaii https://www.hawaiilife.com/blog/ohana-zoning-oahu/

Berkeley regulations on Accessory Buildings for short term rentals https://berkeley.municipal.codes/BMC/23.304.060

Example of prefab ADU https://techcrunch.com/2020/10/20/abodu-seed/

Comments

Post a Comment